Larynx SBSs

|

DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION OF THE LARYNGEAL MUCOSA: The larynx is a tube-shaped organ that connects the pharynx with the trachea. The larynx is part of the respiratory tract and involved in talking and swallowing. The vocal cords, located within the larynx, participate in the production of sound (this is why the larynx is colloquially called the “voice box”). The mucosa of the larynx and vocal cords consists of squamous epithelium, originates from the ectoderm and is therefore controlled from the cerebral cortex.

BRAIN LEVEL: The mucosa of the larynx and of the vocal cords is controlled from the left temporal lobe (part of the sensory cortex). The control center is positioned exactly across from the brain relay of the bronchial mucosa.

BIOLOGICAL CONFLICT: The biological conflict linked to the mucosa of the larynx and vocal cords is a female scare-fright conflict or a male territorial fear conflict, depending on a person’s gender, laterality, and hormone status (see also Flying Constellation). A scare-fright conflict is the female response to unforeseen danger while a territorial fear conflict is the male response to a territorial threat. The conflict can be triggered by any frightening experience.

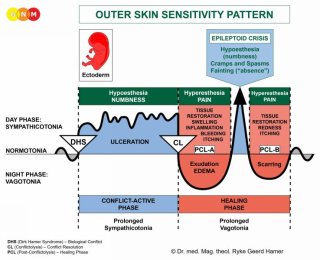

CONFLICT-ACTIVE PHASE: ulceration in the laryngeal mucosa proportional to the degree and duration of conflict activity. The biological purpose of the cell loss is to widen the larynx to allow more air-intake to be better able to cope with the fright.

This brain CT shows the impact of a scare-fright conflict in the area of the cerebral cortex that controls the laryngeal mucosa (view the GNM diagram). The sharp ring structure of the Hamer Focus reveals that the person is conflict active.

HEALING PHASE: During the first part of the healing phase (PCL-A)the tissue loss is replenished through cell proliferation. In conventional medicine, the cell increase is diagnosed as a laryngeal cancer or “throat cancer”. Based on the knowledge of GNM, the new cells cannot be regarded as “cancer cells” since the cell increase is, in reality, a replenishing process.

Healing symptoms are pain due to the swelling caused by the edema (fluid accumulation), difficulties swallowing, coughing, and a hoarse voice or even a complete loss of voice since the vocal cords are affected as well. Depending on the intensity of the conflict, the symptoms range from mild to severe. With an inflammation the condition is called laryngitis, typically accompanied by fever.

After the Epileptoid Crisis, the swelling subsides and in PCL-B the organ slowly returns to its normal function.

What is termed “diphtheria” is, in GNM terms, a healing process in the larynx with the SYNDROME. The concurrent water retention enlarges the swelling and increases the pain; breathing also becomes more difficult.

Vocal cord polyps are hardened squamous epithelial warts that develop as a result of repetitive healing due to conflict relapses. So-called “Singer’s Nodes” are vocal cord nodules caused by injury to the vocal cords because of voice abuse (singing, yelling). In this case, the nodules form as a consequence of the recurring tissue repair - without a DHS.

|

DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION OF THE LARYNGEAL MUSCLES: The larynx consists of an epithelial mucosa and a layer of smooth and striated muscles. The main function of the laryngeal muscles is to regulate the expansion and contraction of the glottis, the vocal apparatus of the larynx with the two vocal cords. The laryngeal muscles keep the glottis open during respiration and more closed during vocalization. The striated part of the laryngeal muscles originates from the new mesoderm and is controlled from the cerebral medulla and the motor cortex. NOTE: The smooth laryngeal muscles are of endodermal origin and controlled from the midbrain.

BRAIN LEVEL: The laryngeal muscles have two control centers in the cerebrum. The trophic function of the muscles, responsible for the nutrition of the tissue, is controlled from the cerebral medulla; the contraction of the muscles is controlled from the left side of the motor cortex (in the temporal lobe). The control center is positioned next to the brain relay of the laryngeal mucosa and exactly across from the brain relay of the bronchial muscles.

NOTE: Inhaling is controlled from the bronchial muscles relay (on the right side of the motor cortex) while exhaling is controlled from the laryngeal muscles relay (on the left side of the motor cortex). Normally these two breathing motions are in balance. This changes if a biological conflict involves one of the two brain relays or both.

BIOLOGICAL CONFLICT: The biological conflict linked to the laryngeal muscles is the same as for the larynx mucosa, namely a female scare-fright conflict or a male territorial fear conflict, depending on a person’s gender, laterality, and hormone status (see also Laryngeal Asthma Constellation, Bronchial Asthma Constellation). The distinguishing aspect of the conflict related to the muscle tissue is the additional distress of “not being able to escape”, “not being able to (re)act”, feeling “rooted to the ground” (petrified), or “feeling stuck” (see skeletal muscles).

CONFLICT-ACTIVE PHASE: cell loss (necrosis) of laryngeal muscle tissue (controlled from the cerebral medulla) and, proportional to the degree of conflict activity, increasing paralysis of the laryngeal muscles (controlled from the motor cortex). The paralysis causes breathing difficulties, explicitly, difficulties exhaling - inhaling is extended because of the reduced function of the laryngeal muscles that control exhaling. If the vocal cords are affected, this causes a voice changes (voice break) or, with an intense conflict, a vocal cord paralysis with an inability to produce sound.

This brain CT shows conflict activity in the laryngeal muscle relay (left side of the cerebral cortex – orange arrows – view the GNM diagram) as well as in the brain relay of the bronchial mucosa (right side of the cerebral cortex – red arrows). The sharp borders of the Hamer Foci reveal that both conflicts, namely a scare-fright conflict and a territorial fear conflict are still active (see laryngeal asthma below). A water or fluid conflict (currently in PCL-A) related to the right kidney parenchyma (lower orange arrows) has already been resolved.

HEALING PHASE: During the healing phase the laryngeal muscles are reconstructed. The paralysis reaches into PCL-A. The Epileptoid Crisis presents as coughing fits with spasms and convulsions of the larynx, equivalent to a focal seizure. A cough that comes from the larynx sounds like “barking” (the expression “kennel cough” points to a scare-fright conflict suffered by animals in the kennel). In PCL-B, the function of the laryngeal muscles returns to normal.

What is termed “spasmodic dysphonia” indicates that the laryngeal muscles as well as the larynx mucosa are in healing. Whooping cough (pertussis) is also such a combined process (see also whooping cough related to the bronchial muscles).

Recurring symptoms or an “allergy cough” are brought on by conflict relapses triggered by setting on a track that was established when the original conflict took place (see allergies).

The Broca’s area or speech center is embedded in the brain relay of the laryngeal muscles (on the left cortical hemisphere). The specific biological conflict linked to the Broca’s center is an inability to speak or speechless conflict, experienced as an acute fright and being “speechless with fear”. This causes during the conflict-active phase speech impairment, precisely, difficulties forming words (compare with Stuttering Constellation). The condition reaches into PCL-A but normalizes after the Epileptoid Crisis (see also stroke and speech impairment).

LARYNGEAL ASTHMA involves two Biological Special Programs (see also bronchial asthma)

In this case, the person is in a Laryngeal Asthma Constellation, also throughout the Epileptoid Crisis which is a temporary reactivation of the conflict-active phase.

The actual asthma attack occurs during the Epileptoid Crisis. The Epi-Crisis of the striated laryngeal muscles presents as convulsions moving inwards. The symptoms of laryngeal asthma are therefore the typical gasping for breath and prolonged inhaling (when the laryngeal muscles are affected, inhaling is extended because of the partial functional loss of the laryngeal muscles that control exhaling). The Epi-Crisis of the smooth laryngeal muscles presents as a spasm, similar to the hyper-peristalsis during an intestinal colic. With concurrent water retention due to the SYNDROME, the asthma attack could be severe.

When both the laryngeal and bronchial muscles go through the Epileptoid Crisis at the same time, the asthma attack presents as prolonged inhaling with gasping for breath (laryngeal asthma) and extended exhaling with wheezing (bronchial asthma). This condition, called status asthmaticus, causes acute breathing difficulties with the danger of dying from suffocation.

NOTE: Cortisone is a sympathicotonic agent that reactivates the conflict-active symptoms. In this case, it causes a paralysis of the laryngeal and bronchial muscles. The antispasmodic effect of the medication can, therefore, be lifesaving. Caution, however, with the SYNDROME, since the water retention increases the swelling in the brain (see brain edema).

Chronic laryngeal asthma attacks indicate that the related scare-fright conflict has not been completely resolved. In conventional medicine, recurring asthma attacks are usually associated with an “allergy”.

Hence, the laryngeal asthma attack involves both the striated and smooth laryngeal muscles. The Epileptoid Crisis of the striated laryngeal muscles presents as laryngeal spasms and convulsions. The Epi-Crisis of the smooth muscles presents as a hyper-peristalsis similar to an intestinal colic. Hence, BOTH the smooth and striated laryngeal muscles take part in the asthma crisis. The same applies to the bronchial asthma attack; in this case, the smooth and striated bronchial muscles are involved.

|