FEMALE BREAST

|

DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION OF THE BREAST GLANDS: Anatomically, the breasts cover the chest (pectoral) muscles in front of the ribs and the sternum. Fat tissue, connective tissue, and ligaments (Cooper’s ligaments) provide support to the breasts and give them their shape. The female breasts are mammary glands that contain in each breast 15-20 lobes comprised of many small lobules. The function of the breast glands is to produce milk to feed young offspring. During pregnancy, hormones such as prolactin change the glandular tissue in preparation for lactation. When a woman breastfeeds her baby, the milk travels through a network of milk ducts to the nipple at the tip of the breast. The nipple is bordered by a dark area of skin, called the areola. In evolutionary terms, the breast glands developed from sweat glands of the corium skin. The nipple is an evagination of the corium skin; this is why both the nipples and the areola are highly pigmented. Like the corium skin, the breast glands originate from the old mesoderm and are therefore controlled from the cerebellum.

BIOLOGICAL CONFLICT: In biological terms, the female breast is synonymous for caring and nurturing. The biological conflict linked to the breast glands is, therefore, a nest-worry conflict concerning the well-being of a loved one (including a pet) or worries about the “nest” itself (distress regarding a woman’s home or workplace). The breast glands also correspond to an argument conflict. Typically, the argument (with a partner, one of the children, a parent, a friend) has a “worry”-aspect.

CONFLICT-ACTIVE PHASE: Starting with the DHS, during the conflict-active phase breast gland cells proliferate proportionally to the intensity of the conflict. The biological purpose of the cell increase is to enhance the function of the breast glands in order to have more milk available when a nest-member is in need (female mammals also nurse the adult males in the event of an emergency). Even if a woman is not breastfeeding at the time or is no longer of childbearing age, her breasts still respond to a worry conflict in this biologically meaningful manner.

With prolonged conflict activity (hanging conflict) a compact nodule develops in the breast (it can also form along the mammary line). Throughout this period, the nursing mother has more milk in the conflict-related breast. In conventional medicine, the growth is called a glandular (lobular) breast cancer or a mammary carcinoma (compare with “breast cancer” related to the milk ducts); if the rate of cell division exceeds a certain limit, then the cancer is considered “malignant”.

Breast cancer in men: Men also have mammary glands, but the breasts remain undeveloped because of their higher testosterone level (in females, estrogen promotes the development of the breasts). However, if a man has a low testosterone level due to an active loss conflict (see testicles) or a conflict-related hormonal imbalance, he can suffer a nest-worry conflict just like a woman. Men usually don’t pay attention to breast nodules, neither do they (have to) go for mammograms, which is why the number of breast cancers found in men is very low. NOTE: Male lactation occurs with a conflict related to the pituitary gland that secretes prolactin, the hormone that stimulates the breast glands to produce milk.

HEALING PHASE: Following the conflict resolution (CL), the cells that are no longer needed are broken down with the help of fungi, TB bacteria, or other bacteria. During this process the tumor is filled with serous fluid and tubercular secretion; at this point, it might be diagnosed as a “cyst” (see breast gland cyst below). Healing symptoms are swelling due to the edema (fluid accumulation) in the healing breast (in PCL-A) and night sweats. With the SYNDROME, that is, with water retention as a result of an active abandonment or existence conflict, the swelling becomes much larger. The repair of the breast tissue is noticeable as sharp pain, which is characteristic for the healing of all old-mesodermal tissues (see shingles). The extent of the symptoms is determined by the degree and duration of the conflict-active phase. Depending on the size of the tumor, the healing process can take several months; with a hanging healing due to conflict relapses even longer. When the healing phase is prolonged, the ongoing decomposing process leads to a loss of breast gland cells. If a woman is nursing at the time, the loss of glandular breast tissue (hypoplasia of the mammary gland) causes a reduction or cessation of milk production in the affected breast (compare with lack of milk production related to the pituitary gland).

Complications with glandular breast cancer arise when the corium skin of the affected breast undergoes a healing phase at the same time (see skin tuberculosis). This happens either with an “attack conflict” triggered, for example, by a breast biopsy or when a woman suffers a “disfigurement conflict” evoked by the appearance of her breast. With a hanging healing the breast oozes constantly (watch the protein loss!) contributing, additionally, to “feeling soiled” conflicts. In this case, surgery must be considered.

The by-products of the cell removal process are eliminated through the lymphatic system. The lymph fluid travels predominantly to the axillary lymph node located in the armpit of the healing breast. Hence, in the healing phase, the lymph node swells up.

Women who have breast cancer often suffer a self-devaluation conflict leading to the development of a lymphoma in the axillary node. In conventional medicine, the new “tumor” is interpreted as a “metastasizing cancer”, based on the wrong assumption that the lymph vessels are pathways for “spreading cancer cells”. If the self-devaluation conflict is more severe, usually following a mastectomy, this affects the sternum or ribs underneath the amputated breast (see bone cancer). The mastectomy could also trigger an “attack conflict” with the development of a melanoma in the area of the surgical scar. Potential complications occur when the fluid from the edema enters the pleural cavity causing a transudative pleural effusion. The self-devaluation conflict (“my breast looks ugly”) could also involve the fat tissue with a localized swelling (see lipoma) in the breast during the healing phase. It is not uncommon that such a growth is misdiagnosed as a breast cancer, or “metastasis”.

After the tumor has been decomposed, a cavern remains at the site (see also lung caverns, liver caverns, pancreas caverns). Calcium deposits on the wall of the cavern show on a mammogram as macrocalcification (compare with microcalcification in the milk ducts). Concurrent water retention due to the SYNDROME inflates the cavern creating a breast cyst (compare with breast cysts in the milk ducts). So-called fibrocystic breasts are the result of recurring healing and scarification processes (PCL-B) in the breast.

If the required microbes are not available upon the resolution of the conflict, because they were destroyed through an overuse of antibiotics, the additional cells remain. Eventually, the tumor becomes encapsulated with connective tissue. Such an encapsulated nodule might be found years later during a mammogram, often with dire consequences.

|

|

DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION OF THE MILK DUCTS: The milk ducts are a structured network of ducts that attach to the lobules of the breast glands. They merge into the main mammary ducts at the nipple. The nipples are small projections of the skin endowed with special nerves making them sensitive to stimuli such as touch. In lactating females, the milk ducts carry milk to nurse the infant. The inner lining of the milk ducts consists of squamous epithelium, originates from the ectoderm and is therefore controlled from the cerebral cortex.

BIOLOGICAL CONFLICT: The biological conflict linked to the milk ducts is a separation conflict experienced as if a loved one was “torn from my breast“ (compare with loss conflict related to the ovaries). Women suffer separation conflicts through an unexpected divorce, a break-up with a partner, her child, a parent, or a friend or when a beloved person (or pet) dies. The fear of a separation can already activate the conflict. Similarly, the milk ducts correlate to the distress of wanting to separate, let’s say, from a spouse or from a parent because of a betrayal, constant fighting, or abuse. The separation from a home (a woman’s “nest”) also corresponds to the milk ducts (compare with nest-worry conflict linked to the breast glands). The loss of the “nest” is the equivalent to the male territorial loss conflict.

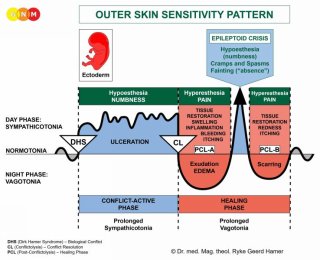

CONFLICT-ACTIVE PHASE: ulceration in the lining of the affected milk duct proportional to the degree and duration of conflict activity. The ulceration occurs in the branches exiting the lobules of the breast glands or in one of the main ducts close to the nipple. A severe separation conflict could involve all milk ducts in the conflict-related breast. The biological purpose of the cell loss is to widen the ducts so that the milk that is no longer required (due to the separation) can drain off easier; the larger lumen of the ducts prevents a congestion of milk in the breast. The ulceration usually goes unnoticed because of the hyposensitivity during the conflict-active phase (Outer Skin Sensitivity Pattern). The loss of sensitivity might reach into the nipple.

With a persistent, intense hanging conflict the continuous ulceration contracts the milk ducts resulting in scirrhotic knots and painful pulling in the breast. The contraction is visible as a local retraction at the breast and an inverted nipple. The affected breast becomes considerably smaller (recurring scarification because of a hanging healing in PCL-B also makes the breast smaller). On a mammogram, a scirrhotic knot might appear in the shape of a compact nodule and subsequently diagnosed as a cancer (“scirrhous carcinoma”), even though there is no “cancer cell” mitosis!

The conflict-active phase is accompanied by a short-term memory loss that reaches into PCL-A. This is characteristic of all separation conflicts (see Biological Special Program related to the skin).

HEALING PHASE: During the first part of the healing phase (PCL-A) the tissue loss is replenished through cell proliferation. The breast is swollen, red, hot, and itchy. When the separation is at the same time associated with the skin, a rash develops also on the breast (see Paget’s disease). In the healing phase the sensitivity returns, markedly with hyperesthesia, a heightened sensitivity to touch, specifically at the nipple. The swelling makes the nipple appear inverted (compare with inverted nipple in the conflict-active phase).

In conventional medicine, the cell proliferation in the milk duct is diagnosed as an intraductal breast cancer, with an inflammation as an inflammatory breast cancer (compare with breast cancer related to the breast glands). Based on the Five Biological Laws, the new cells cannot be regarded as “cancer cells” since the cell increase is, in reality, a replenishing process. A “benign” breast tumor is usually diagnosed as an intraductal papilloma or papillary carcinoma.

With the SYNDROME due to an active abandonment or existence conflict the retained water is exceedingly stored in the healing breast, which increases the swelling. A large swelling might occlude the milk duct. In this case, the discharge produced during the repair process becomes clogged in the breast, particularly behind the nipple. Biologically, this complication is not planned because if a female is nursing, the baby would normally suck the breast dry (adult mammals suck the udder of the female when the milk is congested). In non-lactating women, however, the secretion has no outlet, which increases the swelling and the pain. Dr. Hamer therefore recommends to drain the fluid twice a day with a milk pump or have it sucked out by her partner, a friend, or her midwife since this is less painful (the discharge has a slightly sweet taste like milk). If a cirrhotic breast is not drained during the healing phase, the breast becomes small and hard.

A leaking breast is an indication that the milk duct is not entirely blocked or that the healing process occurs close to the mamilla. The secretion emptying through the nipple is a clear or bloody fluid (compare with smelly discharge when a glandular breast tumor is healing and milky discharge related to the prolactin-producing pituitary gland). With concurrent water retention, the swelling in a milk duct is usually diagnosed as a breast cyst (compare with breast cyst in the breast glands).

Mastitis (periductal mastitis) occurs when the ducts under the nipple become inflamed. Mothers who are separated from their baby, for example after delivery, develop mastitis as soon as they are able to nurse their infant uninterrupted. Lactation mastitis or an inflammation of the nipple (thelitis) is either linked to a separation conflict or, in breastfeeding women, when the nursling is sucking too strong.

The Epileptoid Crisis manifests as acute pain. The pain is not of a sensory nature but a strong pulling pain. Pain also occurs in PCL-B; in this case, because of the scarification process.

After the Epileptoid Crisis, the swelling of the breast goes down.

|